Over the past 150 years, technology has changed beyond recognition – from developing electrical grids to computing in the cloud, from mechanical calculators to artificial intelligence. Yet, the fundamental nature of the people who create these technologies remains remarkably constant. They are, above all, creative scientists.

Which raises a crucial question for modern leaders: if human nature hasn’t changed, why reinvent management practices?

So many organisations struggle to get the best from their technical teams, yet three fundamental principles have been present in the best creative and technical teams of the past 150 years.

Creative problems are never isolated; change one variable, and everything else shifts. Innovators need to see how their work fits into the larger whole.

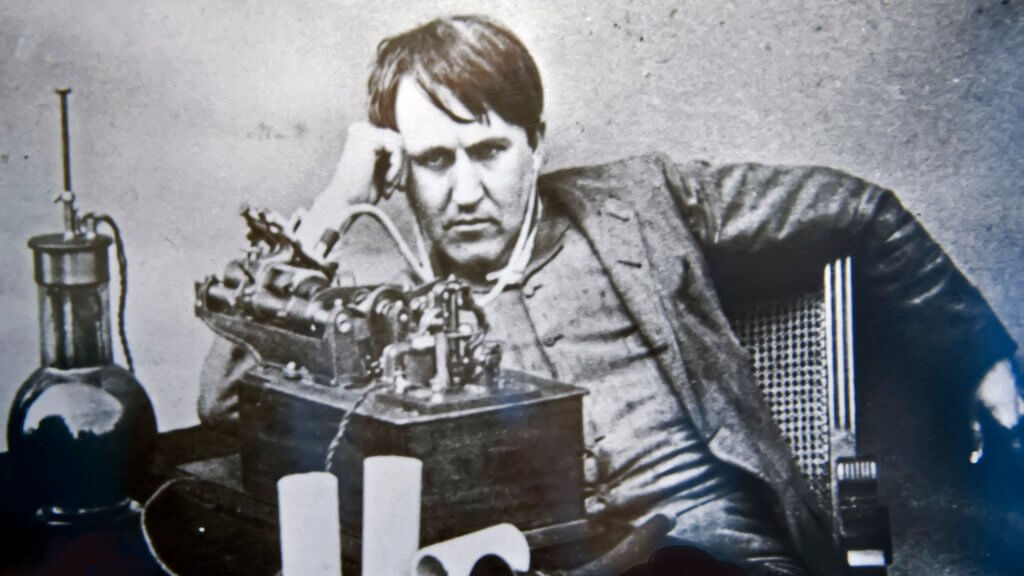

Edison grasped this intuitively at his Menlo Park laboratory in the 1870s. When developing the light bulb, he wasn’t just perfecting a single component, he was designing an entire electrical distribution system. His teams needed to see how filaments, generators, wiring, and safety devices all worked together. This holistic understanding enabled them to solve problems that would have been impossible to address in isolation.

Sixty years later, Robert Oppenheimer faced a similar challenge at Los Alamos. When military leaders tried to compartmentalise work for secrecy, he resisted, knowing that breakthroughs required physicists, chemists, and engineers to share ideas freely.

The principle remains relevant today. Technical systems work best when the people building them understand how their work fits into the larger whole. Teams need access to customer feedback, business metrics, and strategic context, not just technical specifications.

The second principle recognises that physical and social environments profoundly influence how creative teams perform. Edison organised his “invention factory” around the needs of creative minds rather than the convenience of traditional management structures. His teams shared experiments, tools, and failures freely.

Oppenheimer did the same under extraordinary pressure. Despite wartime secrecy, he cultivated what psychologists later called psychological safety: a space where people could challenge ideas, debate openly, and learn together.

No one applied this principle more deliberately than Bob Taylor at Xerox PARC. Taylor’s beanbag meetings and open workspace design were not gimmicks but strategic tools to eliminate hierarchy and invite candour. The results—personal computing, ethernet networking, and the graphical user interface—reshaped modern life.

The pattern is unmistakable: when leaders design environments around trust, autonomy, and open exchange, creativity thrives. When they impose control and bureaucracy, creativity dies.

The question is not whether creative teams will fail, but how they do so – and whether they learn.

Edison framed failure as progress – he hadn’t failed 1,000 times; he’d found 1,000 ways that didn’t work. That mindset defined his teams’ resilience. Modern researchers echo this insight. Harvard professor Amy Edmondson distinguishes “intelligent failures” (which generate learning) from “basic failures,” which result from carelessness. Great teams maximise the former and minimise the latter.

Every innovative system breaks before it succeeds. The healthiest teams fail in controlled ways that yield insight rather than chaos.

The Psychology Behind Creative Management

What Edison, Oppenheimer, and Taylor knew intuitively has since been proven scientifically. Creative people are driven by learning, not performance.

Psychologists distinguish between performance-goal and learning-goal orientations. Performance-goal oriented individuals focus on demonstrating their competence and avoiding failure; they excel in structured, predictable settings. Learning-goal oriented individuals focus on developing their skills and understanding; they embrace uncertainty and see failure as feedback.

Most engineers and inventors are learning-goal oriented. They crave autonomy, challenge, and the freedom to explore. Command-and-control management—so effective for routine work—stifles them. Even small intrusions, like an unnecessary meeting during a breakthrough, can derail motivation.

Leaders who understand this adapt their approach. They provide context and purpose but allow self-direction. They replace top-down control with shared learning.

The Power of Psychological Safety

Carl Rogers first identified psychological safety as essential for creativity in the 1960s, but Edmondson’s research in the 1990s proved importance for team performance. Studying hospital teams, she expected to find that better teams made fewer mistakes, but the best teams reported more errors—not because they made more, but because they felt safe to discuss and fix them.

Google confirmed this decades later with Project Aristotle, which found that team composition mattered less than team climate. The best groups shared two traits: conversational turn-taking (everyone spoke roughly equally) and social sensitivity (team members were good at reading each other’s emotions) – both hallmarks of psychological safety.

Taylor’s PARC beanbag meetings exemplified this approach. Everyone sat in identical seats, eliminating subtle hierarchies. When conflicts arose, he required each side to explain the other’s view until both agreed it was understood. This turned disagreement into discovery.

Such practices allowed extraordinary collaboration among strong personalities – a key reason PARC produced so many world-changing innovations.

A Practical Framework for Leaders

Putting these ideas into practice begins with hiring for curiosity and collaboration, not just credentials. Learning-oriented people light up when asked about a time they failed and what they learned. Edison sought such minds—telegraph operators, machinists, and self-taught experimenters who shared relentless curiosity.

Next, replace bureaucracy with information. Give teams direct access to customer feedback, business metrics, and strategic goals so they can act with confidence. Autonomy works only when paired with clear context. Leaders become conductors rather than controllers, guiding rhythm and direction without playing every instrument.

Finally, institutionalise intelligent failure. Celebrate well-designed experiments, share lessons from mistakes, and design systems that make reversibility easy.

The Enduring Wisdom of Human-Centred Management

The most striking lesson from 150 years of creative enterprise is how little the fundamentals have changed. The technologies differ, but the human needs behind them—safety, curiosity, autonomy, and purpose—are constant.

Modern leaders don’t need new management fads. They need to rediscover what history’s most successful innovators already knew: creativity flourishes where people understand the system, trust their environment, and are free to fail intelligently.

Jamie Dobson is the founder of Container Solutions and author of ‘The Cloud Native Attitude’ and the recently published ‘Visionaries, Rebels and Machines: The story of humanity’s extraordinary journey from electrification to cloudification’.